SC victims of COVID won’t be here to make favorite holiday dishes, but left recipes behind | Raskin Around

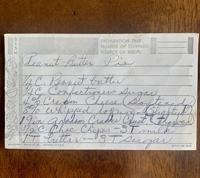

It didn’t matter how many caramel cakes, swirl cookies, brownie bars or puddings were on the buffet at Carey Lynch’s house. Lynch knew that nobody at her family reunion could walk the sweets line without taking at least a sliver of her peanut butter pie, leaving nothing but graham cracker crumbs for her young granddaughters to fight over.

That didn’t sit right with Lynch, a lifelong believer in the goodness of sugar. As the adults picked up their plates, Lynch pulled the girls aside and whispered that she’d baked another pie just for the two of them. It was hidden under the table.

A concealed backup pie is the epitome of comfort food. A familiar, uncomplicated dish that arrives at a moment of worry to take all concerns away. Certain items tend to get namechecked in comfort food discussions, but the category is intensely personal. Fried plantains with cheese, cinnamon sweet rice and burnt toast all count. Everyone’s idea of comfort food is a little different.

What is the same for most people at the end of 2020 is how much they need their comfort foods now. A national study commissioned this summer by a St. Simon’s Island mozzarella stick maker revealed Americans are eating comfort food meals five times a week. EatingWell recently reported that users of the magazine’s recipe database have embraced the search term “just like grandma’s.”

During the holiday season, those cravings can usually be taken offline. Grandmas, grandpas and other much-loved home cooks spend December bustling about the kitchen, making their friends and relatives’ favorite soul-soothing dishes.

This year, though, the country has lost more than 300,000 people to the coronavirus, including more than 4,700 South Carolina residents, many of which were over age 50. They won’t be here to make comfort foods for their families.

Lynch died of COVID-19 on Oct. 16. Her great-granddaughter will make her peanut butter pie for Christmas, using the recipe she’s guarded fiercely since inheriting it as a junior high schooler.

“There are certain recipes that become important to families,” explained Eve Slaughter, who for years tried to get her niece to share the pie recipe with friends who asked for it. “But this Christmas, it’s going to have a whole new meaning, for sure.”

The recipe follows, along with holiday recipes from three other South Carolinians who died of the coronavirus. Each one reflects a lifetime and, their contributors know, an expression of love for those within it.

Ed Bengivenga died on Aug. 20 after testing positive for COVID. Provided

Edward Bengivenga, Rock Hill

The first time Kristy Bengivenga tried to kiss her future husband, he turned his head away.

“He was a handyman by trade, so for my birthday, he was going to redo my cabinets,” Bengivenga said of the man who was then just her friend from church. As he worked in her kitchen, amid three dozen detached cabinet doors that had been off their hinges for the better part of a year, she thought to herself, “If I don’t jump on this man…”

Even though Edward Bengivenga rejected her initial advance, the two got married later that year. Their son was born in 2010; Bengivenga had two daughters from a previous marriage.

Kristy Bengivenga likes to refer to her late husband as the family’s rock.

“Our roles were a little reversed,” she said. “He did the cooking and cleaning and I worked. He was a 6-feet, 350-pound tough guy, so you never know.”

Edward Bengivenga didn’t read other people’s recipes and didn’t write down his own. Still, he could assemble a lasagna to enchant his granddaughters and every year insisted on making their holiday meals. Kristy Bengivenga would sometimes chip in a side dish of carrots or store-bought apple pie, but her husband prepared the turkey, stuffing, rigatoni and pumpkin pie.

There was always enough food to keep people at the table. “He loved the family being at the house,” Bengivenga said.

Bengivenga himself was “pretty much a homebody,” so it was surprising when he showed symptoms of coronavirus the day after his son’s birthday this summer. Kristy Bengivenga suspects he contracted the virus on trips to a home improvement store: Perpetually eager to be helpful, he was renovating his mother’s bathroom before he was hospitalized.

Edward Bengivenga died of COVID-19 on Aug. 1. He was 55.

Alice Warren died on Oct. 24 after a COVID diagnosis. Provided

Alice E.M. Warren, Charleston

For at least a few years in downtown Charleston, it would have been easier to count the people who hadn’t ever sampled Alice Warren’s cooking than those who knew her red rice and fried chicken by heart. Between 1969 and 2003, she worked at The Ladson House, Alice’s Restaurant, and Alice’s Fine Foods, feeding just about everyone in town.

“She learned by doing,” former colleague Martha Lou Gadsden, who went on to open Martha Lou’s Kitchen, told The Post and Courier. “She started from scratch and she worked hard.”

Still, when it came to holiday baking, she preferred to let her friend’s son Antwan Smalls handle it.

Smalls in 2014 opened My Three Sons in North Charleston, the site of Warren’s last restaurant assignment. Health problems forced her out of the kitchen, although community members sometimes asked for small catering favors.

“Even up to the time she couldn’t do it anymore, they were still calling for little things she could fix from home; red rice mostly, collard greens, pork chops and cornbread,” Marie Brown, another one-time Ladson House employee, told The Post and Courier.

According to Smalls, Warren’s own request was for his carrot cake at Christmastime. “She would always compliment me on my baking skills,” he said.

Warren died of COVID-19 on Oct. 24. She was 74.

Richard Proia with his chicken marsala. Provided

Richard Proia, Columbia

Richard Proia was a stickler for the rules. Not the unspoken rules favored by the rigid and high-strung. Even if other adults obeyed a made-up rule that you shouldn’t ride the same Coney Island roller coaster over and over, Proia wasn’t about to go along with it.

The rules that Proia admired were the rules written by leagues, commissions and federations. He was so conversant in rules of sports he didn’t play that he was unbeatable at the board game he did, the aptly named Rules of the Game. For fun, he umpired recreational baseball.

He liked it better than accounting, which he did by day, but Proia’s daughter says the appeal of both roles was the same. He liked neat systems.

“Around 2005, he randomly decided ‘I’m going to take up cooking,’ ” Angelina Proia said. “He bought every spice he could and alphabetized everything.”

Right away, Richard Proia started recreating dishes he’d been eating since he was a kid in Rochester, N.Y. Proia was one of 11 children, so he had a knack for dishes designed to stretch, such as a pasta casserole he dubbed “crazy lasagna” and manicotti made with a version of his mother’s red sauce. He made chicken Marsala, chicken cacciatore and baked ziti. Angelina Proia remembers the dishes because her father liked to recount them.

“One of the things that drove me nuts is he just wanted to talk about how good this was, and what he did to make it so good,” she said.

Proia and his first wife divorced in 2013. He and his second wife bought a home in Columbia, but he was on a spring trip back to Rochester when he started feeling disconcertingly weak. In those early days of the pandemic, neither Proia’s family nor doctors pushed for a test. Days later, he was found delirious in his apartment with a 103-degree fever.

Proia died of COVID-19 on Apr. 16. He was 66.

This photo of Carey Lucille Lynch was taken in 1942. Her younger sister decades later remembered the dress, telling Lynch’s granddaughters that Lynch “loved wearing pretty clothes.” Provided

Carey Lucille Garrett Lynch, Greenville

“You never knew what she was going to say,” Amy Howe said of her grandmother, whose sunbright independent streak never dimmed.

Carey Lucille Garrett Lynch, one of 13 children born to a Piedmont, S.C. carpenter and his wife, learned to swim when she was in her 40s. She started driving around the same time. At 90, when she moved to Pawley’s Island to be closer to her son, she decided she wanted to be called “Carey” after a lifetime of being known as Lucille.

What was consistent about Lynch, besides her affection for her family, was her fondness of sweets.

“Mama (Cille) would cook all the dishes, but she really had some amazing desserts,” Howe’s sister, Eve Slaughter, says. “A decadent chocolatey dessert was a given: Even in the morning, when you spent the night, you got sugary cereal.”

At Christmas, in addition to giving toys to her granddaughters, Lynch gave each of them a Whitman’s Sampler. The iconic box of candies was more commonly exchanged by grown-ups in love or domestic trouble, but Lynch thought the girls deserved caramels and nougat and cherry cordials.

Still, the present that meant the most to them was one they couldn’t quite remember receiving. A satin-trimmed, quilted baby blanket. Howe’s was yellow and Slaughter’s was green. They carried their blankets with them to college.

“It became part of our lives,” Slaughter said, adding that they never mistook their blankets for mere pieces of fabric.

After she was hospitalized for the coronavirus, Lynch told Howe, “I have had so much love in my life because I gave so much love.”

Lynch died of COVID-19 on Oct. 16. She was 96.